Web Scraping#

The process of retrieving data displayed on websites automatically with your computer is called web scraping. It means instead of clicking, selecting and copying data yourself, your python script does it for you. You would only need to define how and where to look. Scraping information from the internet can be very time consuming, even when your machine does it for you. However, it may also be very rewarding because of the vast amount of data and possibilities - which come for free.

Before we can turn to the actual scraping online, we will deepen our understanding of html and how to navigate through a file.

Xpath#

The Extensible Markup Language XML provides something like a framework to markup languages to encode structured, hierarchical data for transfer. It is thus a related to HTML, just less for displaying data than storing and transferring it. While the differences are not of interest here (learn about them yourself anytime, though), the similarities are: in the way, we can use them to navigate html documents.

The XML Path Language (Xpath) allows to select items from an xml document by addressing tag names, attributes and structural characteristics. We can use the respective commands to retrieve elements from html documents, i.e. websites.

The two basic operators are

a forward slash

/: to look into the next generationsquare brackets

[]: select a specific element

The forward slash works basically the same way as in an URL or path when navigating a directory on your computer. The square brackets on the other hand have a very similar functionality to the usage of square brackets in python.

Lets have a look at a slightly extended version of the html document from the previous chapter to see how we can use these operators for navigation.\

As usual, we first import the package (actually only one class for now) providing the desired functionality: Scrapy

from scrapy import Selector

my_html = \

"""<html><body><div id='div_1'><p class='parag-1' id ='intro'>This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>

<p class='parag-1-1' id ='main'>Part 2.</p></div id='div_2' href='www.uni-passau.de'>

<p class='parag-2' id ='outro'>Part 3. <a href='www.uni-passau.de'>Homepage</a></p></body></html>

"""

#formatted version to better visualise the structure

# <html>

# <body>

# <div id='div_1'>

# <p class='parag-1' id ='intro'>

# This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.

# </p>

# <p class='parag-1-1' id ='main'>

# Part 2.

# </p>

# </div id='div_2' >

# <p class='parag-2' id ='outro'>

# Part 3.

# <a href='www.uni-passau.de'>Homepage</a>

# </p>

# </body>

# </html>

Because of the tree like structure elements are labeled in on the basis of a family tree.

The html consists of the body inside the html tags.

In the next generation, called child generation, we see one div element, itself containing two p elements, i.e. children.

Another p element appears as a sibling to the only div element.

Now let’s select single elements from this html using the xpath() method to which we pass our statement as string. To do so, we must first instantiate an Selector object with my_html. Note that chaining the extract() method to the selector object gives the desired result.

sel = Selector(text=my_html)

# navigate to p elements inside div

print('both p elements:\n', sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p').extract())

both p elements:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>']

In the special case here, where all child elements are the p elements we are looking for, we can use the wildcard character *. It wil select any element, no matter the tag in the next generation (or in all future generations with a double forward slash).

# use wildcard character *

print('\nwildcard *:\n', sel.xpath('/html/body/div/*').extract())

wildcard *:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>']

To select only the first p element, index the result with square brackets.

:class: caution

Xpath indexing starts with 1 and not 0 like python does!:::

Another way is to use scrapy's ```extract_first()``` method.

# select first p with [1]

print('slelect only first p\n',sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p[1]').extract())

# indexing the python list starts with 0!

print('\nslelect only first p\n',sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p').extract()[0])

# with extract_first()

print('\nslelect only first p\n',sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p').extract_first())

slelect only first p

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>']

slelect only first p

<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>

slelect only first p

<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>

We see, that a forward slash navigates one generation deeper into the structure, from html over body and div to both(!) p elements. Here, we get back a list (first print statement) of the p elements, where we can intuitively use the square brackets to select only the first one.

What we get back, however, is still a selector object. To extract the text only, we need to modify the statement further by /text().

# select text from first p element

to_print = sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p[1]/text()').extract()

print('text in first p:\n',to_print)

text in first p:

['This is a brief introduction to ', '.']

Now again, we do not see all of the text, just the string before the b tags and the dot after it as elements of a list. Even though the b tags for bold printing appear in-line, they still define a child generation for the enclosed ‘HTML’ string. Here, we could navigate further down the tree using a path to the b element for exampe.

Instead, we will make use of the double forward slash //, which selects everything ‘from future generations’. Meaning it will select all the text from all generations that follow this first p element.

# select text from first p element and all future generations by a double forward slash

to_print = sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p[1]//text()').extract()

print('text in first p and future generations with double slash:\n',to_print)

# for one string, use the join() function

print('\ncomplete string:\n', ''.join(to_print))

text in first p and future generations with double slash:

['This is a brief introduction to ', 'HTML', '.']

complete string:

This is a brief introduction to HTML.

Beside specifying a path explicitly, we can leverage built-in methods to extract our desired elements. Scrapy’s getall() returns all elements of a given tag as list

print('scrapy:\n', sel.xpath('//p').getall())

scrapy:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>', '<p class="parag-2" id="outro">Part 3. <a href="www.uni-passau.de">Homepage</a></p>']

As mentioned before, elements can be addressed using attributes, like ID or class name. The attribute is addressed in square brackets, with @attr = 'attr_name'. If the same attribute applies to several tags, a list of all results is returned.

# search all elements in document (leading //*) by id

print('ID with wildcard:\n', sel.xpath('//*[@id="div_1"]').extract())

# same as (tag must be known)

print('\nID with div:\n', sel.xpath('//div[@id="div_1"]').extract())

ID with wildcard:

['<div id="div_1"><p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>\n<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p></div>']

ID with div:

['<div id="div_1"><p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>\n<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p></div>']

The contains function provides access to attributes based on (parts of) the attribute name.

# find all elements where attr contains string

print('contains string:\n', sel.xpath('//*[contains(@class, "parag-1")]').extract())

contains string:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>']

Finally, an attribute can be returned by addressing it in the path.

print('get attribute:\n', sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p[1]/@id').extract())

get attribute:

['intro']

CSS#

The Cascading Style Sheets language is another way to work with markup languages and thus html. Of special interest for us is that it also provides selectors. Even more convenient is that scrapy includes these selectors and the respective language. CSS uses a different syntax, which can offer much simpler and shorter statements for the same element than xpath (or sometime, the opposite)

The basic syntax changes from xpath like this:

a single generation forward:

/is replaced by>all future generations:

//is replaced by a blank space (!)not so short anymore: indexing with

[k]becomes:nth-of-type(k)

For scrapy, nothing changes really, except using .css() method. The selector object is the same as before.

Some examples:

# navigate to p elements inside div

print('xpath:\n', sel.xpath('/html/body/div/p').extract())

print('\ncss:\n', sel.css('html>body>div>p').extract())

# navigate to all p elements in document

print('\nall p elements')

print('xpath:\n', sel.xpath('//p').extract())

print('\ncss:\n', sel.css('p').extract())

xpath:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>']

css:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>']

all p elements

xpath:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>', '<p class="parag-2" id="outro">Part 3. <a href="www.uni-passau.de">Homepage</a></p>']

css:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>', '<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p>', '<p class="parag-2" id="outro">Part 3. <a href="www.uni-passau.de">Homepage</a></p>']

The css locator provides short notation when working with id or class:

to select elements by class: use

tag.class-name(similiar to method chaining)to select elements by id: use

tag#id-name

Examples from the toy html above:

# select by id

print('select by class:\n', sel.css('*.parag-1').extract())

# select by id

print('\nselect by id:\n', sel.css('*#intro').extract())

select by class:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>']

select by id:

['<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>']

Attributes are in general addressed by a double colon ::attr(attribute-name), for example to extract a link from the href attribute:

# select by attribute

print('\nselect by attribute:\n', sel.css('*::attr(href)').extract())

select by attribute:

['www.uni-passau.de']

The double colon is also used to extract ::text, like we used /text() in xpath:

# extract all (blank space!) text descending from p elements inside div elements with class 'div_1'

print('\nextract text:\n', sel.css('div#div_1>p ::text').extract())

extract text:

['This is a brief introduction to ', 'HTML', '.', 'Part 2.']

Look for exampe at this cheatsheet for more commands with xpath and css.

Lastly, let’s look at BeautifulSoup again. It offers basically the same functionality to address and select any element based on its tag or attributes, but can make life easier with its prewritten methods. Keep in mind however, that BeautifulSoup is a python package, while the xpath and css syntax is standalone and will thus transfer to other software, e.g. R.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(my_html)

# select by id

print('by id:\n',soup.find_all('div', id='div_1'))

# select by class

print('\n by class:\n',soup.find_all('p', class_='parag-1')) # note class_ (not class)

# by s

by id:

[<div id="div_1"><p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>

<p class="parag-1-1" id="main">Part 2.</p></div>]

by class:

[<p class="parag-1" id="intro">This is a brief introduction to <b>HTML</b>.</p>]

Inspecting a webpage#

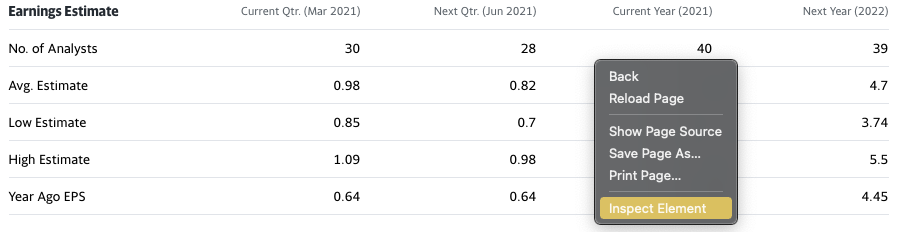

Common internet browsers like firefox, chrome, safari, etc. include functionality to inspect webpages, meaning to look at the underlying html. To view the html, right-click on a specific element on the webpage, e.g. a headline, and select “Inspect Element” (or something similar), like shown in this screenshot taken from this page:

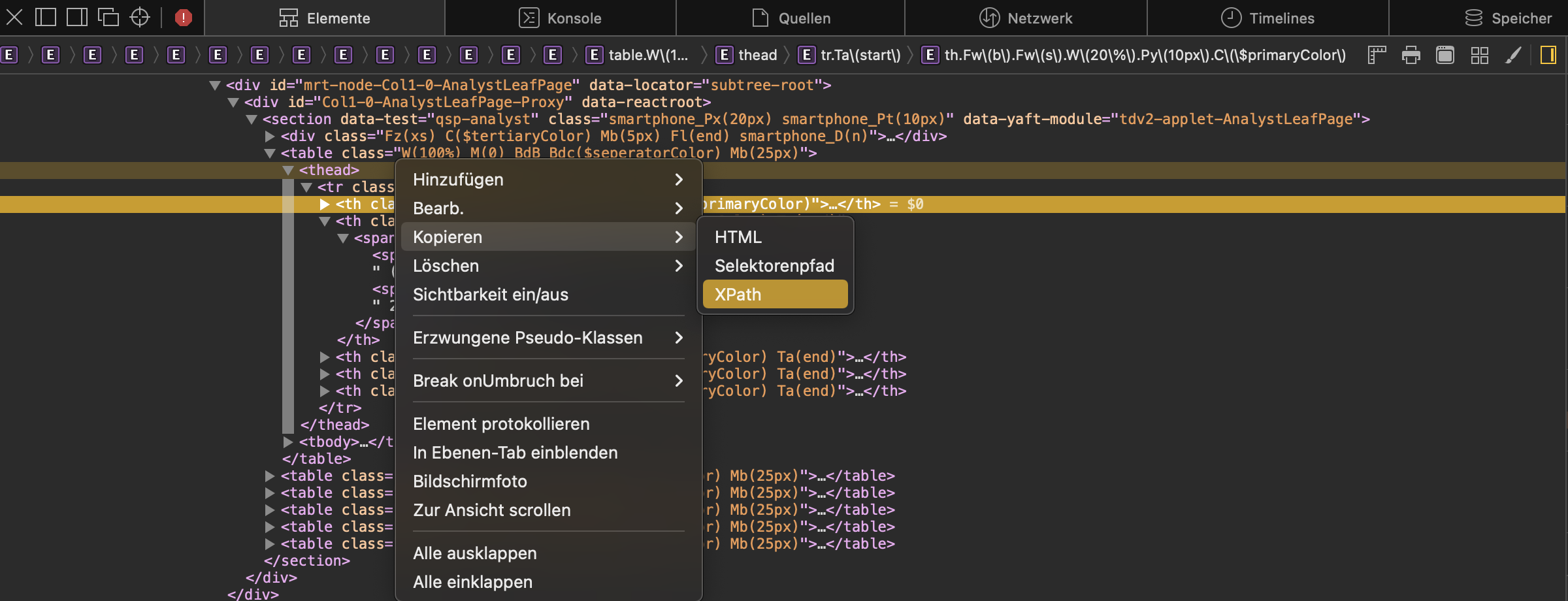

You will then see a small window open at the bottom of your browser, showing the html in hierarchical structure where elements can be expanded to show its child generations:

While hovering with the mouse over

an element from the list, your browser should highlight the respective element on the website. So hovering over the <table> element will highlight the complete displayed table, while hovering over a <tr> element will only highlight a specific row of the table. This facilitates the setup of your code for selection. Furthermore, a right-click on the element in the list let’s one copy several characteristics like the path or the attributes directly to avoid spelling or selection errors.

In this example, we see that information is stored in a <table> and we could select it by specifying the data-reactid’ (we would have to check if there are more elements of this class, tough ids should generally be unique).

In order to collect the displayed information, we use the methods from before.

scrapy selector#

import requests as re

from scrapy import Selector

headers = {

"User-Agent":

"Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/44.0.2403.157 Safari/537.36"

}

url = 'https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/AAPL/analysis?p=AAPL'

response = re.get(url, headers=headers)

response.ok

False

sel = Selector(response)

column names:

# select column names based on order, as no id is given for the tables

columns = sel.xpath('//table[1]/thead[1]/*').css(' ::text').extract()

print(columns) # unfortunately gives unsatisfying result with parentheses

[]

# filter by hand...

columns = [el for el in columns[1:] if any(['Year' in el, 'Qtr.' in el])]

print(columns)

[]

table data:

# select table entries based on data-reactid

table_body = sel.xpath('//table[1]/tbody/*').css(' ::text').extract()

print(table_body)

[]

labels = [el for i, el in enumerate(table_body) if i%5==0]

data = [el for i, el in enumerate(table_body) if i%5!=0]

{labels[x]:[el for el in data[x:x+4]] for x in range(len(labels))}

{}

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame.from_dict({labels[x]:[el for el in data[x:x+4]] for x in range(len(labels))},\

orient='index', columns = columns)

df

pandas#

The read_html()function returns a list of all available tables when we pass the response object as argument.

pd_df = pd.read_html(response.content)

print(f'type: {type(pd_df)}, length: {len(pd_df)}')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In [26], line 1

----> 1 pd_df = pd.read_html(response.content)

2 print(f'type: {type(pd_df)}, length: {len(pd_df)}')

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/util/_decorators.py:331, in deprecate_nonkeyword_arguments.<locals>.decorate.<locals>.wrapper(*args, **kwargs)

325 if len(args) > num_allow_args:

326 warnings.warn(

327 msg.format(arguments=_format_argument_list(allow_args)),

328 FutureWarning,

329 stacklevel=find_stack_level(),

330 )

--> 331 return func(*args, **kwargs)

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/io/html.py:1205, in read_html(io, match, flavor, header, index_col, skiprows, attrs, parse_dates, thousands, encoding, decimal, converters, na_values, keep_default_na, displayed_only, extract_links)

1201 validate_header_arg(header)

1203 io = stringify_path(io)

-> 1205 return _parse(

1206 flavor=flavor,

1207 io=io,

1208 match=match,

1209 header=header,

1210 index_col=index_col,

1211 skiprows=skiprows,

1212 parse_dates=parse_dates,

1213 thousands=thousands,

1214 attrs=attrs,

1215 encoding=encoding,

1216 decimal=decimal,

1217 converters=converters,

1218 na_values=na_values,

1219 keep_default_na=keep_default_na,

1220 displayed_only=displayed_only,

1221 extract_links=extract_links,

1222 )

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/io/html.py:1006, in _parse(flavor, io, match, attrs, encoding, displayed_only, extract_links, **kwargs)

1004 else:

1005 assert retained is not None # for mypy

-> 1006 raise retained

1008 ret = []

1009 for table in tables:

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/io/html.py:986, in _parse(flavor, io, match, attrs, encoding, displayed_only, extract_links, **kwargs)

983 p = parser(io, compiled_match, attrs, encoding, displayed_only, extract_links)

985 try:

--> 986 tables = p.parse_tables()

987 except ValueError as caught:

988 # if `io` is an io-like object, check if it's seekable

989 # and try to rewind it before trying the next parser

990 if hasattr(io, "seekable") and io.seekable():

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/io/html.py:262, in _HtmlFrameParser.parse_tables(self)

254 def parse_tables(self):

255 """

256 Parse and return all tables from the DOM.

257

(...)

260 list of parsed (header, body, footer) tuples from tables.

261 """

--> 262 tables = self._parse_tables(self._build_doc(), self.match, self.attrs)

263 return (self._parse_thead_tbody_tfoot(table) for table in tables)

File ~/Desktop/Lehre/python_class/venv.nosync/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/io/html.py:618, in _BeautifulSoupHtml5LibFrameParser._parse_tables(self, doc, match, attrs)

615 tables = doc.find_all(element_name, attrs=attrs)

617 if not tables:

--> 618 raise ValueError("No tables found")

620 result = []

621 unique_tables = set()

ValueError: No tables found

pd_df[0]

| Earnings Estimate | Current Qtr. (Sep 2023) | Next Qtr. (Dec 2023) | Current Year (2023) | Next Year (2024) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No. of Analysts | 27.00 | 24.00 | 35.00 | 35.00 |

| 1 | Avg. Estimate | 1.39 | 2.10 | 6.06 | 6.56 |

| 2 | Low Estimate | 1.35 | 1.72 | 5.82 | 5.60 |

| 3 | High Estimate | 1.45 | 2.41 | 6.17 | 7.09 |

| 4 | Year Ago EPS | 1.29 | 1.88 | 6.11 | 6.06 |

Webcrawler#

A webcrawler or spider will automatically ‘crawl’ the web in order to collect data. Once set up, it can be run every day in the morning, every couple of hours, etc. Such rugular scraping is used to build a database, e..g with newspaper articles. Commonly, for this kind of data collection, the webcrawler is deployed using cloud computing which is not part of this course.

We will, however, take a look at a very basic spider not diving in too deep. In scrapy, spiders are defined as classes including the respective methods for scraping:

providing the seed pages to start

parsing and storing the data

It is important to note that scrapy spiders make use of callbacks. A callback is a function, which is run as soon as some criterion is met, usually when some other task is finished. In a scrapy spider, the parsing function is used as callback for the request method: The request must be complete so that the parsing may commence.

callback#

The following is a basic example for a callback. The function will print the string and the callback will print the length of the string.

def enter_string(string, callback):

print(string)

callback(string)

def print_len(x):

print(len(x))

enter_string('onomatopoeia', callback=print_len)

onomatopoeia

12

Let’s take a look at the basic structure of a spider, found in the scrapy docs.

import scrapy

scrapy.spiders.logging.getLogger('scrapy').propagate = False # suppress logging output in cell

class mySpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "my_first"

custom_settings = {

'REQUEST_FINGERPRINTER_IMPLEMENTATION': '2.7',

}

def start_requests(self):

urls = [

'http://www.example.com'

]

for url in urls:

yield scrapy.Request(url=url, callback=self.parse)

def parse(self, response):

print(response.css('p::text').extract())

The start_requests method provides the start or url or seed. For every url in this starting list, we send a Request using the respective function. We provide to this function the callback to be the parse method defined subsequently. It is important to use yield, i.e. to create a generator, as this is required by scrapy.

In parse(), we use the already familiar css method to extract all text found in p elements from the website.

In order to let the spider crawl, we need to import CrawlerProcess instantiate an according object, link the spider to it and start the process.

from scrapy.crawler import CrawlerProcess

proc = CrawlerProcess()

proc.crawl(mySpider)

proc.start()

['This domain is for use in illustrative examples in documents. You may use this\n domain in literature without prior coordination or asking for permission.']

After some output (red window), we see the text from the website.

In order to really crawl the web, we would need to extend the spider:

find all links on the starting page

parse all text on the starting page

find all links on the pages found the step before

parse all text from the pages found the step before

then repeat steps 3 and 4.

We will now expand the spider from above to print the text from the starting page, then follow the provided links to the next page and print that text.

from scrapy.crawler import CrawlerProcess

import scrapy

scrapy.spiders.logging.getLogger('scrapy').propagate = False # suppress logging output in cell

class followSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "my_second"

custom_settings = {

'REQUEST_FINGERPRINTER_IMPLEMENTATION': '2.7',

}

def start_requests(self):

urls = [

'http://www.example.com'

]

for url in urls:

yield scrapy.Request(url=url, callback=self.parse_links)

def parse_links(self, response):

links = response.css('a::attr(href)').extract()

print(''.join(response.xpath('//p/text()').extract()))

for link in links:

yield response.follow(url=link, callback=self.parse)

def parse(self, response):

print(response.url)

print(''.join(response.xpath('//p/text()').extract()))

proc = CrawlerProcess()

proc.crawl(followSpider)

proc.start()

This domain is for use in illustrative examples in documents. You may use this

domain in literature without prior coordination or asking for permission.

http://www.iana.org/help/example-domains

As described in and , a

number of domains such as example.com and example.org are maintained

for documentation purposes. These domains may be used as illustrative

examples in documents without prior coordination with us. They are not

available for registration or transfer.We provide a web service on the example domain hosts to provide basic

information on the purpose of the domain. These web services are

provided as best effort, but are not designed to support production

applications. While incidental traffic for incorrectly configured

applications is expected, please do not design applications that require

the example domains to have operating HTTP service.The IANA functions coordinate the Internet’s globally unique identifiers, and

are provided by , an affiliate of

.

Writing several parse functions may also be necessary when dealing with ‘nested’ websites: One parse function may extract a specific block from an overview page, the other from all children of the overview pages.

We used the scrapy.follow method, to go to the next link. Using this method enables us to write the parse method recursively, i.e. the spider would not stop until arriving at a page with no links. Thus, in order to set up a functional spider, not only the webpages must be selected accordingly, but one should always include some filters before starting the spider and storing the scraped data.